TINKUS - 2007

Yocona Centro

Uluchi

Macha

As the crops ripen in Northern Potosí, the Aymara communities know it is time to thank the Pachamama (Mother Earth) and petition Her for plentiful harvests to come. These communities, called Ayllus, are the very basic political and social units of originary Andean society. They are communities of extended families; like concentric circles they expand from a single family to larger communities of Ayllus. These communities of hard working farmers plant crops of corn, potatoes, grains and legumes, and have herds of lamas, sheep, goats and cattle that need to be pastured daily and brought back to their corrals at sundown, making their working day up to fourteen hours long.

In the Gran Ayllu of Macha, all its lesser Ayllus gather for a sacrificial ceremonial dance / battle, an “encounter”: Tinkus. It is a ritual battle with the purpose of shedding human blood in offering to the Pachamama as payment and to assure rain and plentiful harvests for the benefit of all. This ancient pre-Incan ceremony was adopted by the Inca, influenced in colonial times by Christianity and European culture, and in the present day by modern and postmodern culture. This fusion and overlay of distinct influences is in evidence in its present form: traditional, colonial and contemporary.

Tinkus is performed on the third of May, the Day of the Cross. Serving many purposes, it creates and regenerates the Aymara universe, beliefs and traditions through a series of sacrifices and offerings to the Pachamama. In the three-day ceremony the participants offer their blood, wealth, dance and hardship. The ceremonies begin in each lesser Ayllu, two days before the Tinkus ceremony.

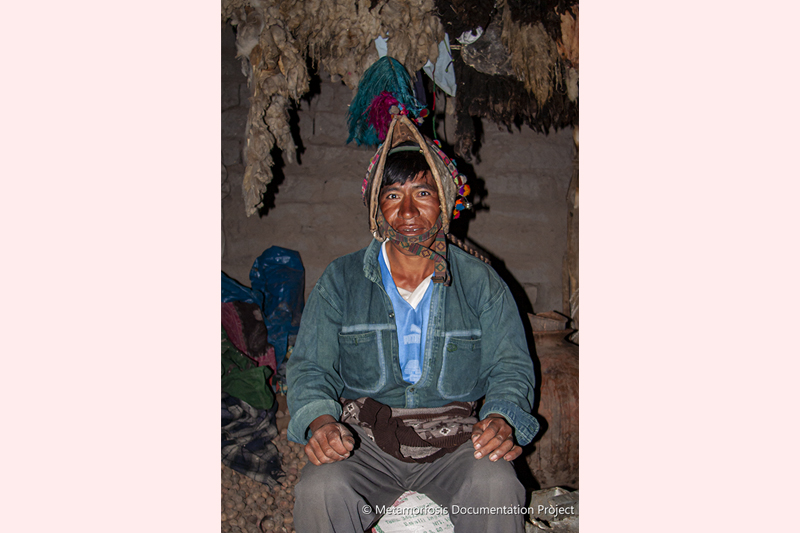

We documented these pre-ceremonies in Yocona Centro, part of the Ayllu of Uluchi of the Great Ayllu of Macha. Every year, in each lesser Ayllu, a family is chosen to sponsor the feast for their community. The head of the sponsoring family is the Pasante; he is in charge of the celebrations and is responsible for the community’s patron saint. The patron saint of each lesser Ayllu is the Taita Santa Vera Cruz (Father True Holy Cross), a wooden Christian cross with a Christ-like head, no body, and the traditional helmet and garments of the Tinkus. This cross, devoid of the sacrificed body of Christ, was introduced by the Catholic priests so as not to encourage human sacrifice. During the three-day ceremony these crosses are revered, danced with and carried by the communities to all the rituals and ceremonies.

At the Pasante’s house, almost simultaneously in all the Ayllus of the municipality, the ceremonies start with the announcement of the festivities: two explosions of dynamite in the vicinity of the house. As people slowly gather, the preparations for the ceremony get underway. The women gather outside the inner courtyard walls around a fire to prepare the food for the feast, peeling large amounts of potatoes. The men gather around cleaning the courtyard, playing charangos (a small stringed instrument), bringing the sacrificial lamas to a close-by corral, uncovering the big ceramic pots where the grain beer (chicha) was brewed and preparing the small rock-table altar in the courtyard.

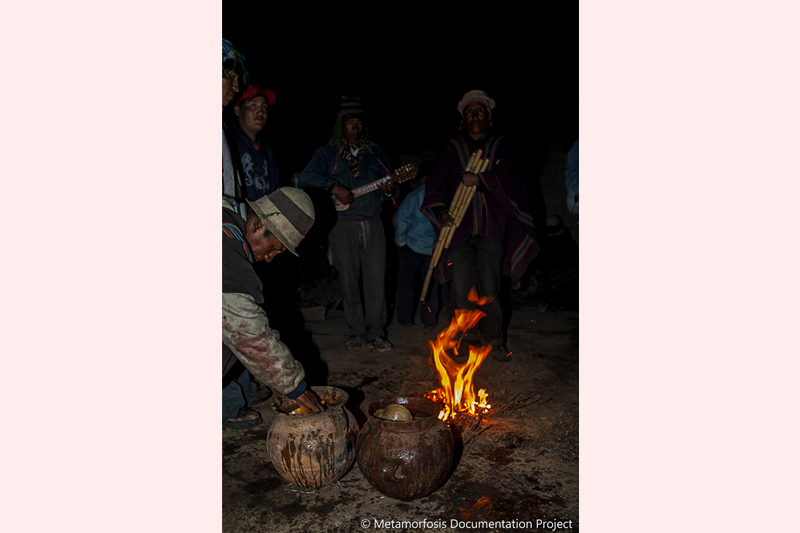

As the sun sets the Challa begins with the ritual drinking of the chicha, the offerings at the altar and the sharing of the sacred coca leaves.

As the courtyard gets soaked from the offerings of chicha, the lamas are brought in and sacrificed, the blood flowing from their necks directly onto the ground. It is said that the lamas are sacrificed so the Pachamama will be pleased and spare the lives of humans in the Tinkus. Two lamas are sacrificed, one black and one white, one male and one female, emphasizing the duality which is intrinsic in the Andean cosmovision. As the lamas are bleeding on the ground they are covered; the male with a poncho, the female with an embroidered shawl.

Two groups of men, with the assistance of several women and children, then perform the ritual skinning and gutting of the lamas. The meat is prepared for cooking; the heart and liver are boiled separately. Meanwhile, more ceremony is underway. The wife of the Pasante scoops warm blood out of the wound on the neck of one of the lamas, and smears it on the cheeks of the faces of all present, a protection against evil. Also, one of the men who had been skinning a sacrificial lama takes the skin and playfully tries to put it on the other participants of the ceremony as if it were a cape (This is reminiscent in a way of Xipe Totec of Mesoamerica, where a priest wears the skin of a sacrificed Teotl Ixiptla [god impersonator]). When the lamas’ hearts and livers have been boiled, they are cut into small pieces and distributed by one of the elders to all present, bare hand to bare hand, to be eaten as a blessing.

The sound of the jula julas (wooden flutes) signals the beginning of the dancing, which will continue throughout the night, interspersed at frequent intervals with men passing chicha and women passing lama stew to all the community. The ritual drinking during these three-day ceremonies takes an enormous toll on the participants, and their recovery takes weeks. It is important to realize that all the drinking is not enjoyable, and is, in fact, a sacrifice. Another aspect of the sacrifice is the offering of the continuous dancing, almost without rest over the three days, all done with the same sense of responsibility and reciprocity to Mother Earth.

The Catholic Church, as it has done for centuries, tries to suppress these ceremonies, and it is common for the priest to send threats to the communities. These threats have intensified since a new indigenous priest arrived at the parish in Macha. It is also notable that this priest rents beds in the church’s old dormitories to the groups of tourists that come to the Tinkus. In our stay with the community of Yocona Centro, the rituals were interrupted by the reading of a letter sent by the priest to the community. The priest threatened a fine of 500 Bolivianos (a month’s wages) to every single person that attended the Tinkus. He also threatened to stop coming to their community’s church to perform mass, baptisms or weddings.

The communities dance all night in circles in the courtyards of the all lesser Ayllus. They mix different forms of footwork, all allegoric of amphibians and reptiles: El Sapo, La Serpiente, La Salamandra, El Lagarto (The Bullfrog, The Serpent, The Salamander, The Lizard).

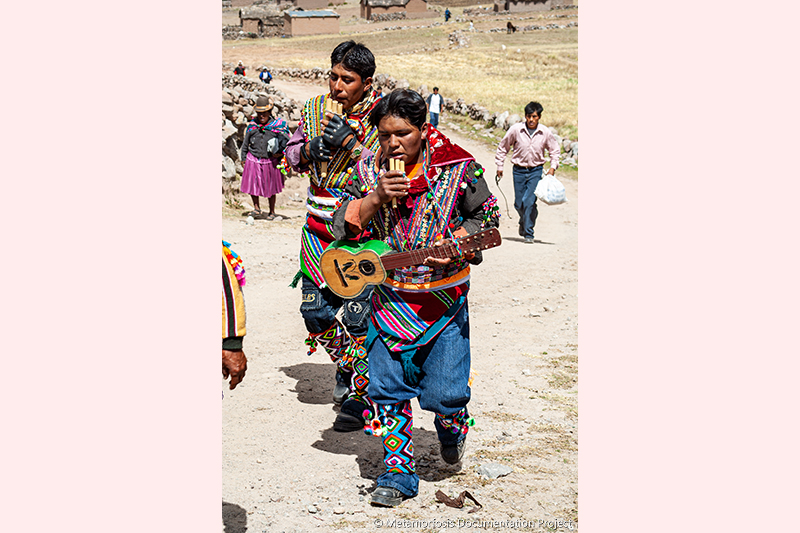

The next day, and without resting, the people from the lesser Ayllus walk/dance and gather around the church of their Ayllu and dance most of the day there. In the afternoon, after mass during which the crosses are blessed, couples are married and children are baptized; they walk/dance, some of them all night, to arrive in Macha the next morning for the Tinkus.

The ritual space is created, and it is recreated from the smallest of Ayullas, to the lesser Ayllus and finally to the Great Ayllu of Macha. Through this encounter, their universe and relations are renewed, disputes are solved, and the bonds between communities are reinforced.

The town of Macha is located in the province of Chayanta, in the municipality of Colquechaca in the north of the department of Potosi. With a population of about six hundred people, it swells during the ceremony of Tinkus to between four and six thousand, most of them participants in the ceremony.

In pre-Incan times this area was an Aymara lordship or kingdom known as Qaraqara. The place where the Macha church and plaza are located was an ancient Waca or sacred ceremonial place. The people of this region were warring societies, and when the Inca colonized the area they were recruited into the Incan army. It is said that the best warriors of this area were the Inca’s personal guards, and were hand-picked from the best fighters in the Tinkus. Notably, the first indigenous revolt against Spanish rule in Bolivia was led by Tomás Katari, a native of Macha.

As the different Ayllus enter the center of Macha, they dance in circles in the four corners of the plaza; this dance is repeated over and over by different groups at different times all through the coming day and night, creating and recreating the ritual space. Once they have performed a few of these dances in both directions, they break rank, and as a platoon they dance / march to the next corner where the dance is once more performed. The constant circling of the plaza, the ceremony’s center, with the hypnotic sound of the jula julas, the alcohol and the tiredness of already two days of dancing and not sleeping transport the participants to an altered state of consciousness that readies them for the ultimate sacrifice, their blood.

Occasionally during the morning, following the traditional forms and under the watchful eye of the military police, canchas (courts) are created; empty spaces in the crowds where participants from two communities challenge each other to fistfight.

Meanwhile, the rest of the communities continue dancing corner to corner, around the plaza.

Men as well as women fight in this ceremony, hand to hand, one to one, man to man, or woman to woman.

These violent ceremonies have a bonding effect in the larger community, as disputes are resolved and different families' ties are strengthened by the honor of having fought each other in honor of the Pachamama. This violent ceremony is devoid of anger and hatred; it is sacred, altruistic violence.

It happens very naturally at first. One person from one community challenges someone from another community, and, after the capitanes and the military police agree that it is a fair encounter, the fighters shake hands, hug and start punching to the face in ritual-like movements.

The fight goes on until one person falls to the ground, or one is bleeding profusely, or one can’t fight any more. The women and the capitanes, with their whips, stop the fight and also keep the participants from fighting outside the prescribed protocol. After the fight the fighters shake hands and hug again.

Until recently, people fought with hard leather helmets and gloves sometimes laced with metal shards, or with rocks tied to their hands, to assure plenty of blood as a sacrificial offering. Now days, with the presence of the military police in the town to prevent casualties (three people die each year, on average), the participants’ gloves are removed and they are not allowed to tie rocks on their hands. As a result the use of the protecting helmets is waning in popularity and changing the visual appearance of the dance. It is said that in ancient times a Tinkus was not successful unless at least one person died. With the government prohibition of human sacrifice, when someone is killed in the Tinkus, the body is secretly buried during the night.

This intrusion of the military police is making the dance evolve in other ways, as more fights happen in the side streets and around the river bank, away from the police - and sadly, away from the ceremonial center of the plaza.

There comes a moment in the Tinkus ceremony when the fighting becomes a frenzy, and it becomes generalized, community against community, not one to one anymore. Called Tinkus Cha'jua, it is more dangerous. The capitanes lose control, and people can be more severely injured. It usually happens in the late afternoon, and the military police respond using tear gas to break up the fighting crowds.

The ceremony continues all day and through the night. The next morning people are still circling the plaza, stumbling around as they attempt to dance with the same bravado as the day before. After it is all over, they start the long walk back to their homes. Some Ayllus are twenty or more kilometers from Macha, and some people, tired from the three days of dancing, drinking and fighting, just sleep by the side of the road. Back in their Ayllus, a new Pasante is chosen in each community, and the Cross is passed to him (hence the name Pasante) to care for until the next year’s Tinkus. The community members resume their daily routine and hard work, knowing that the Pachamama was served, and that existence is assured for another year.

© Armando Espinosa Prieto.